I spend a lot of time thinking about marine planning and management. And as we all know, one of the best ways to learn is to look at the past. So this thought has reminded me of a study I did a few years ago in Istanbul, Turkey – a review of planning and managing a very important estuary in the middle of this enormous city. That, and my case study was just chosen as a highlight for UNEP’s Rapid Response Assessment for World Environment Day (on June 5th)!

The Golden Horn Estuary, once “the most romantic waterway in Europe,’’ suffered through 40 years of uncontrolled industrial and urban growth after World War II. Basically, someone decided that it would be a great idea to concentrate industry on the shores of this Ottoman playground and cultural centre for ease of waste disposal. So 1/3 of the estuarine surface area was filled – that’s staggering! With the factories came an incursion of tenement homes with zero infrastructure planning, let alone a waste disposal system. Ironic, since the Golden Horn may have been the site of the world’s first environmental management program in the 1450s (Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror limited settlement, and mandated forestation and re-use of pottery materials).

The Golden Horn Estuary, once “the most romantic waterway in Europe,’’ suffered through 40 years of uncontrolled industrial and urban growth after World War II. Basically, someone decided that it would be a great idea to concentrate industry on the shores of this Ottoman playground and cultural centre for ease of waste disposal. So 1/3 of the estuarine surface area was filled – that’s staggering! With the factories came an incursion of tenement homes with zero infrastructure planning, let alone a waste disposal system. Ironic, since the Golden Horn may have been the site of the world’s first environmental management program in the 1450s (Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror limited settlement, and mandated forestation and re-use of pottery materials).

I’ll leave the gory details to my paper (here or email me for a copy), but suffice it to say that the estuary was an ecological and human health disaster for decades, although not for a lack of planning attempts by the city and business owners. I do have to mention that the hydrogen sulfide stench was enough to bowl you over, especially on a hot summer day.

I’ll leave the gory details to my paper (here or email me for a copy), but suffice it to say that the estuary was an ecological and human health disaster for decades, although not for a lack of planning attempts by the city and business owners. I do have to mention that the hydrogen sulfide stench was enough to bowl you over, especially on a hot summer day.

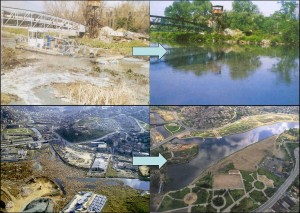

Then in 1984, everything changed. A new mayor strengthened the water and sewerage administration and passed a restoration plan with 100% city council approval. They demolished and relocated 620 industries, 1200 shops, and 5000 homes along the shores and nearly finished the wastewater collection and removal infrastructure in just a few years. With a mayoral shift in 1989, however, progress was stalled until environmental management was again deemed important following the next change in power. The sewage system was then completed, 5 million cubic meters of anoxic sludge was dredged from the estuary (that’s a lot) through an innovative process, a floating bridge that impeded water circulation was removed, and cultural and social facilities were established.

The estuary rebounded spectacularly and local mentality changed along with it. I asked someone why he picked up his post-picnic trash (Istanbullus are notorious for leaving it), and was told that he thinks of the estuary as a valuable resource now that it is clean again. It certainly helped that the city launched a massive campaign to promote its good deeds. This photo shows Mayor Gurtuna about to jump into the Golden Horn – an entirely unthinkable act just a few years earlier. Note the substantial news presence documenting his swim. And even more convincing was the discovery of seahorses living in the estuary a few years ago – a very pollution-phobic creature!

The estuary rebounded spectacularly and local mentality changed along with it. I asked someone why he picked up his post-picnic trash (Istanbullus are notorious for leaving it), and was told that he thinks of the estuary as a valuable resource now that it is clean again. It certainly helped that the city launched a massive campaign to promote its good deeds. This photo shows Mayor Gurtuna about to jump into the Golden Horn – an entirely unthinkable act just a few years earlier. Note the substantial news presence documenting his swim. And even more convincing was the discovery of seahorses living in the estuary a few years ago – a very pollution-phobic creature!

My point is this: I don’t know the answer for how to fix British Columbia’s marine planning and management problems, but I know what worked (and didn’t) for Istanbul. These two places couldn’t be more different, but maybe some lessons can translate. Managing the Golden Horn was only successful after decisive actions were taken by a strong leader with environmental health, and thus long-term community health, as the primary goal. We could also use stronger management authority and a solid 20 year plan. Mayor Dalan’s 1984 plan was developed with heavy input from scientists that directed the water and sewerage administration and acted as secretary general of the municipality, as well as from business owners (although he had some very strong and powerful opponents). Mayor Gurtuna relied upon engineers to devise new technology for a more successful dredging operation than the old standbys. And of course we could use more community support, maybe encouraged by government “bragging” about successful programs.

But one thing that was left out of Istanbul’s planning process was real community involvement. That’s the role that PacMARA is trying to fill. We want to facilitate members of all kinds of communities (federal and provincial governments, First Nations, coastal communities, industries, commercial and recreational fishing, etc.) to work together to better plan and manage our resources.

We all know this, but it’s good to re-enforce these thoughts every once in a while with examples from other times and places.

– Heather Coleman, Science Advisor

Photo credits: ISKI (the Istanbul Water and Sewerage Administration), http://nomasliteraturblog.wordpress.com/2009/11/28/karawanen-des-orients-unterwegs-auf-legendaren-handelsrouten/.